Sabine: Eberhard, you are here as a representative for the Vedanta teachings. For those who have little experience with Indian philosophy, could you briefly explain what the Vedanta is all about?

Eberhard: I would like to first say that I do not see myself as a representative of a certain philosophical system. I was able to spend a time in India studying and learning with some very practical and true-to-life teachers, and it was there that I was inspired by the wisdom of the Vedanta texts. What leads me to feel that I have no strong single philosophical direction is that the wisdom is so universal and can be found in numerous cultures. The focus of the texts is how to deal with human suffering, namely, how does human suffering arise. What distinguishes the texts from others is that they dont go too deep into the individual's history, because it is believed that the real cause of the problem is found elsewhere.

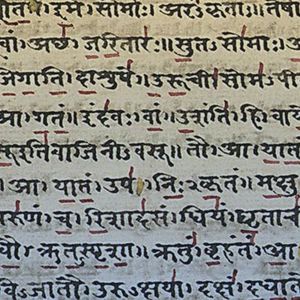

This aproach thus completely contradicts our usual point of view, in which we see the reasons for our suffering almost exclusively within ourselves or in the world around us. While many of us would see this as a very common perspective, they are described in the wise writings of the Indian Vedanta as a self-centered view. The Vedanta texts contrast this purely personal perspective with a counter-perspective - which is in itself equally valid as a perspective. This means that the texts do not claim to identify truth and there are no instructions or rules on how to shape my life. What the texts offer is simply another point of view, which in a way opens up the possibility of looking at things differently. This is already expressed by the Sanskrit word "Darshana," which means intuition, a term which shows up often in Vedanta texts such as the Upanishads or the Bhagavad Gita. At the end of the day, it is about making a very conscious shift in perspective - which can also be very helpful in everyday life when, lets say when we've run out of ideas for a solution to a problem.

Sabine: You mention texts like the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. While no one can really say how old they are, there is no doubt that these texts are very old. Depending on the source, the Bhagavad Gita is estimated to have been written between 500 BC and 300 AD, so it has been around for a good two thousand years. How relevant are these texts for us in modern times? Are they something that can offer me something in my daily life here and now in the 21st century?

Eberhard: These texts have no "expiration date" because they deal with human suffering, which is universal and goes a layer above contexts such as culture. They address man as a single individual, indifferent to concepts such as gender, origin, religion or culture. This means that these texts of wisdom may not speak to the person full of mind chatter, but rather the conscious person, who has the ability to become aware of his thinking. Everything that we use to define or identify us, usually as a result of thought, is referred to in the Patanjali Yoga Sutra as "Vrtti", or, whirlings of the mind. The term includes all thoughts that label me or the world around me. The suffering that I experience from a personal point of view is always connected with a certain identification with one of these labels, which ultimately arises from mind chatter. When in your subconsciousness or in an unaware state, however, you can't see this. These wisdom writings - like the Yoga Sutra - remove me from the outside world, where I see all the problems, to the inner world, in order to strengthen my power of discernment in this way. This finally allows me to see what is really an outer and what is an inner problem. This kind of self-inquiry can increasingly lead to the somewhat disturbing but at the same time liberating realization that the real problem is only myself. This problem, which is regarded as the real and only cause of human suffering in the Indian wisdom texts, is in Sanskrit called "Avidya", or ignorance.

Sabine: My knee-jerk reaction to the notion that I am the root of my suffering is rather unsettling. What does this mean? Can I actively do something to change this ignorance, or must I accept that it is part of the human condition?

Eberhard: On one hand, it does sound disturbing, but on the other hand, it's a disconcerting feeling that I am the problem because I can no longer blame anyone for my suffering. It is of course also unpleasant, because it means that I now have to question my ideas and beliefs about myself and the world. But when you think about it, it also makes so much sense. If I didn't feel that there was another way to live, why would I keep on reading books on yoga and spirituality? My teacher told me, "If it makes no sense, throw it away, but do not throw it away just because you do not like it". This combination of meaning and rejection can mentally uplift you or even sometimes provoke a sleepless night full of contemplation. But this is only a sign that the knowledge is working in me. The awareness that the real problem lies within me opens up completely new options: the possibilities to create solutions to external problems are very limited. I cannot change other people or create a just and peaceful world. But when I become aware of my own inner confusion, or a negative emotion like anger, I can work with the help of the tools of yoga. This does not make everything easy at all, but I have a place within me where all possibilities are open to me and I am limited by nothing more than myself. This is exactly what is called freedom in this context. When it comes to ignorance, you can't eliminate it. Conversely, deliberate actions which arise from my own subjective value-system will add to this state of ignorance further. If I can become aware of my ignorance instead of being proud of what is "known", then I have taken the first step towards inner wisdom. We can't really do away with ignorance, either. It occurs because we each have a subjective value system in which we justify our actions. What we can do is become aware of our ignorance rather than presuming that you know better. This is the first step towards inner wisdom.

Sabine: Can you give me a concrete example of how these philosophical texts can be applied to my daily life? Or an example that helps to point out how they are relevant in daily life?

Eberhard: In these text, inner speed is regarded as a demonic force (asura), while slowness is regarded as a divine strength (deva). When I think to an time when I have a negative emotion, I feel that things are moving around within me so quickly and I feel tightness and closed. I can't recall a single time that I slowly got angry. Conversely, during an experience such as an embodied yoga practice, I feel that things are moving slowly, and I feel expansive and openness.

When I am angry with someone, my intellect jumps out like a vicious dog chained to a leash and ready to strike, biting straight through to the root of where my anger begins. My full attention is directed immediately outward and I am not able to identify this inner speed and tightness. If instead I can rein in my unbridled reaction to my feelings by consciously slowing down the movements of my mind in everyday life, just like during a yoga practice, I might start to make a realiziation and see my own confusion or misunderstanding, as opposed to bringing my focus directly on the external reasons for my anger. This gives me the opportunity to put the problem into perspective and to explore to what extent I am actually feeding the problem through my outward expression of anger and negative emotions. Once I have acknowledged my own confusion, I might even notice that I had in fact overreacted.

This is only one example of how to put this knowledge into practice. My teacher always said spiritual understanding that is not put into use is worthless. He would also always say that I didn't have to believe him. He simply gave me tips and tools to experiment with and to see if they actually worked, with the goal of finding clarity and calm in trying situations. The one quote from my teacher that really stick out in my mind is: "You have the choice not to be upset." It took me 30 years of unnecessary anger to actually listen to this advice.

Sabine: You have referred to different quotes from your teacher - which were probably part of a greater dialog on larger themes. Is dialog particularly important in dealing with the philosophical texts you mentioned? Are these texts perhaps even intended to be read and received together merely because of their genre?

Eberhard: These types of texts are described in India with the Sanskrit word "Pramana", which means "means" or "medium". They are a means of getting past what actually stands between me and my happiness. In a typical situation where someone might ask what that actually is, I would have a very drawn-out answer to describe how I myself and the world around me are the causes of my suffering. In other words, using my intellect, I would start to justify my suffering. The wisdom texts, on the other hand, maintain that the only thing that stands between me and my happiness is ignorance, and in order to be happy I have to develop more clarity. In this case, I do not use my intellect to justify my suffering, but rather to liberate it. This is also why it is called "wisdom" as opposed to "intelligence". This type of knowledge is not intended to be studied in the usual sense or to be recited. Instead, it's more like you take a good hard look at yourself in the mirror and realize your ignorance. This is the starting point from which wisdom takes place.

Sabine: At first sight, many of the texts seem incredibly dense in content and sometimes very difficult to understand. A newcomer who does not know anything about this kind of philosophy, might ask themselves: "Can I really trust myself in a seminar without any previous knowledge?", or "What if I ask a 'stupid' question? ", or " Will I ever understand any part of this? ". How would you address these concerns for those new to these teachings? Are these appropriate for a beginner or is it better to sit with the material on my own for a while first?

Eberhard: I think that beginners can benefit from coming to events. As for the question of understanding, I do not see any problems. Actually, I would argue it might be quite the opposite. If you look more closely, the actual knowledge conveyed in the text it terribly simple. It's kind of frightening, because this simplicity is something that our intellect has a hard time appreciating it. My entire life suddenly appears before me and brings everything to light in such a simple way. Many of us assert that we are deliberately working to avoid feeling discomfort and that the sole purpose of this work is to feel comfortable, without exception. This is a radical statement and it should not go unquestioned. It ought to be explored in detail to understand whether this statement is even true. In this kind of self-study, aided by spiritual calmness and clarity which I, for instance, may experience from the practice of yoga, there is the possibility that I notice something is off with that conjecture - a process which is also known as knowledge.

Often, precisely these questions, which people frequently think are silly or banal, lead to the essential wisdom of these texts in a "satsang", or, a meeting of a group of people interested in self-study to discuss the essential wisdom of these texts in a collective setting. When reference to everyday life situations that include grief and worries, or joy and happiness, is made, then it makes it much lighter to access the knowledge. A satsang is not the same as a teaching, in that it is not that the teacher holds the knowledge that the students do not have. Rather the inherent knowledge which exists in each of us is awakened and allowed to take space, as opposed to being hidden behind a wealth of complications such as identity, social conditioning or self-regulation. Just by looking into the mirror of this wisdom can reawaken this knowledge, which I wish for myself and every one of us.

Sabine: I believe that anyone who has participated in one of your seminars will agree hands-down that your approach is very much practice-oriented and will vouch for your description. If you haven't yet had the chance to participate, I would highly recommend it! Thank you very much for your time and helping us to maneuver through this complex and exciting introduction to Vedanta philosophy!

Eberhard Bärr

Eberhard Bärr

Dr. Sabine Nunius

Dr. Sabine Nunius