Development of the Tattvas

Tattva can be translated as "reality" or "principle" and refers to the elements or building blocks of existence. In non-dual Shaiva Tantrism, the entire reality is seen as a manifestation of the Divine, and these Tattvas are the stages or aspects of this divine manifestation.

The concept of Tattvas slowly developed as early as in the Upanishads and the early Sāṁkhya philosophy. Various concepts merged in the different streams of that time—around 1000 BCE to 0 CE.

In the mature Sāṁkhya philosophy, as seen in the Sāṁkhya-Kārikā, 25 Tattvas increasingly crystallized. The classification, names, and meanings became so influential in further Indian philosophy that they were widely adopted.

Tantrism also builds on these 25 Tattvas, adopting their names, sequence, and largely their basic meanings. However, it expands them towards the subtle or divine by adding 11 more elements. As a result, the 25 Tattvas of Sāṁkhya philosophy are given a more gross material classification than in Sāṁkhya philosophy alone.

36 Tattvas as a Core Element of Kashmir Shaivism

Kashmir Shaivism is a school of Tantra that focuses on the non-dual polarity of Śiva and Śakti and their aspects. This philosophical orientation is known for its detailed elaboration of the 36 Tattvas. Here, the Tattvas form a core concept.

However, the concept of Tattvas can also be found in other tantric traditions:

- In Shaktism, which worships the goddess Śakti, there is also a system of Tattvas, though the number and interpretation can vary.

- Similarly, in Vaishnavism, another major stream of Hinduism that worships Vishnu and his avatars, there are similar cosmological systems, though they are usually not as elaborately detailed as in Shaiva Tantra.

The fundamental concept behind the Tattvas—that the entire reality consists of various principles or aspects ranging from subtle to gross—is a common feature of many Indian philosophical systems. However, the specific formulation and number of Tattvas can vary from tradition to tradition.

In addition to the Hindu traditions, similar concepts are also found in Buddhist Tantra, albeit with different interpretations and practices. Overall, the Tattva concept is an example of how Indian spiritual traditions have developed a complex view of the nature of reality and consciousness, encompassing both philosophical and practical spiritual dimensions.

Tattvas as Creation and Liberation

In non-dual Shaiva Tantrism, the entire reality is seen as a manifestation of the Divine. The Tattvas are the stages or aspects of this divine manifestation. The following sections will explore the two fundamental processes through which these Tattvas unfold and merge back together: the sequence of creation (Sṛṣṭi-Krama) and the sequence of return (Saṁhāra-Krama).

Sequence of Creation (Sṛṣṭi-Krama)

- From unmanifest to manifest: In Shaiva Tantrism, the entire reality is viewed as a manifestation of the Divine. The Tattvas, which range from the unmanifest Śiva to the gross material earth, represent the various stages or aspects of this divine manifestation.

- Correspondence: This sequence symbolizes the process of creation within the philosophical tradition, with the Divine contracting into increasingly denser material forms.

Sequence of Return (Saṁhāra-Krama)

- From manifest to subtle: On our spiritual journey, which aims at liberation or return to the source, we traverse the Tattvas in reverse order. Starting with the gross material earth, we move towards increasingly subtler forms.

- Goal: This sequence illustrates the path of return to the source, where the densifications of the material gradually dissolve, bringing the subtle back into focus.

Paramārtha - The Secret Tattva No. #0

Only in the esoteric non-dual tantric sources is a Tattva No. #0, a secret Tattva, revered. It is considered the key to understanding non-dual Tantra philosophy and is referred to by many names, such as Paramārtha or Śrī Paramaśiva.

It is characterized by the following features:

- Positioning: Tattva #0 does not stand at the top of the hierarchy. In the ranking of the Tattvas, the absolutely transcendent Śiva occupies the highest place.

- The Highest Principle: Although Śiva is considered the "highest" Tattva, Tattva #0 is the highest principle, the ultimate truth (paramārtha). It is not transcendent, for transcendence would mean going beyond it and thus excluding it.

- Inclusion and Transcendence: In the non-dual understanding, the highest must both transcend and include all things. This presents a central paradox.

- Expression and Substance: Tattva #0 expresses itself as the very substance of all things and is simultaneously more than just the sum of all perceivable realities.

- Undefinable Essence: This absolute principle cannot be included in the list of Tattvas, as it penetrates both manifest and unmanifest things as an undefinable essence.

- Incomprehensibility to the Mind: For the human mind, this principle remains absolutely incomprehensible, as it eludes rational grasp.

Śuddha Tattvas (Pure Tattvas)

The five Śuddha Tattvas represent the "Pure Universe." This is not a physical locality, but the absolute reality that permeates the entire manifest universe.

The top five Tattvas are not separate entities but different aspects of the unified divine consciousness, which together offer a differentiated description of the Divine. We can view them as a specific phase or level in the consciousness of the Divine, with differences primarily lying in perspective and emphasis.

Thus, the meditative realization of each of these five Tattvas leads to complete liberation and spiritual awakening.

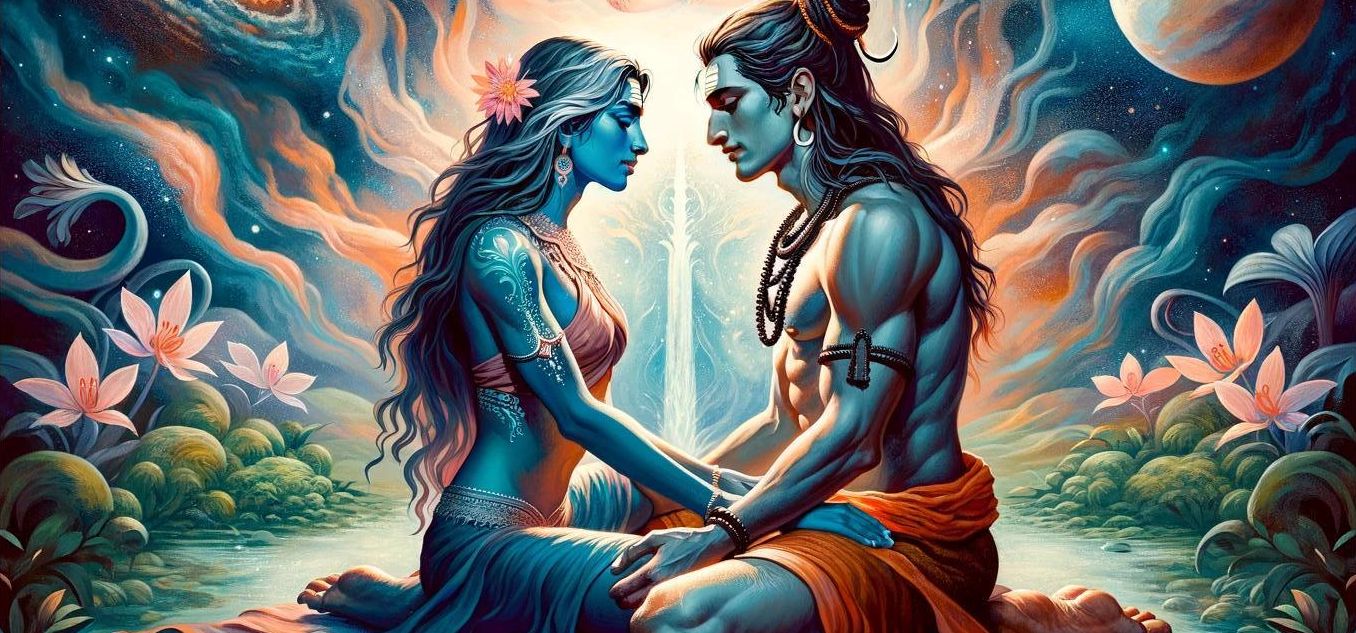

The Five Śuddha Tattvas Begin with the Non-dual Polarity of Śiva and Śakti:

(1) Śiva

In the Pratyabhijñā school, Śiva is understood as the light of manifestation (prakāśa) or the light of consciousness (cit-prakāśa). He symbolizes the illuminating power of consciousness, which manifests in all things and enlightens them.

In the Vijñāna Bhairava Tantra, Śiva is described as the fundamental being that provides coherence to all things and in which all things rest. His existence transcends all definable qualities, and he is seen as the unifying force of all the various Śaktis, the potentials, and energies.

As kuleśvara, the lord of the family, and as the central axis of the revolving wheel of forces, Śiva holds these potentials together and provides space for their unfolding.

(2) Śakti

Śakti is considered in the Pratyabhijñā philosophy as the blissful, self-reflective consciousness (vimarśa). She is the force that allows consciousness to turn back on itself, become aware of itself, and enjoy itself. This dynamic energy is often summarized as cid-ānanda (the bliss of consciousness) and plays a central role in the manifestation and experience of the Divine.

Since Śiva would have no tangible presence without the forces of consciousness, bliss, and will, Śakti is often revered as the highest principle in the non-dual Śaiva tradition. She is the manifestation of the divine energy that permeates and animates all aspects of the universe.

The Triad as the Second Part of the Śuddha Tattvas

The Śuddha Tattvas continue in a triad that forms the basis for the self, the external world, and self-perception:

(1) / (3) Sadāśiva Tattva: Differentiation and Willpower

The principle that takes the very first step towards differentiation, while distinction and identity only arise with Māyā. This is the seed of the universe, which develops from itself through divine willpower (icchāśakti) or the original impulse for self-expression.

(2) / (4) Īśvara Tattva: Personal Deity and Knowledge Power

Īśvara Tattva, defined as "Personal Deity and Knowledge Power," refers to the concept of a personalized deity in spiritual philosophy. The term Īśvara is non-sectarian. As such, it is also mentioned in the Yoga-Sūtra of Patañjali.

Many monotheistic religions recognize this level as the highest reality, where God exists as a personified reality, bearing specific characteristic qualities. This deity is worshiped under various names in different cultures, such as Krishna, Allah, Avalokiteśvara, Yahweh, or Jehovah.

A central aspect of Īśvara Tattva is its connection to jñānaśakti, the power of knowledge. Īśvara is attributed with knowing the subtle pattern used in the creation of the universe. This knowledge power gives Īśvara profound insight into the nature of the universe and its functioning.

(3) / (5) Śuddhavidyā Tattva: Pure Mantra Wisdom and Power of Action

Śuddhavidyā Tattva represents the level of pure wisdom. This Tattva is deeply intertwined with the essence and function of mantras. The word "Vidyā" itself refers not only to wisdom in the traditional sense but also to mantras.

The wisdom relates to the various phases of consciousness of Śaiva-Śakti, which in turn manifest in seventy million mantras. The number seventy million is a mythological figure representing all the mantras that have ever existed or will exist.

In the tantric tradition, mantras are regarded as conscious entities, similar to angels in Western religions. The transformative power of mantras is central; they bring about change and thus express kriyāśakti, the power of action. This power of action demonstrates how mantras act through their transformative effect.

Those who attain liberation on the level of Śuddhavidyā Tattva transform into mantra-beings. In this view, personal spiritual transformation and the energetic impact of mantras are closely intertwined.

Śuddhāśuddha Tattvas (Mixed Tattvas)

The mixed Tattvas (Śuddhāśuddha Tattvas) comprise the next group of Tattvas, which are partly pure and partly impure. They represent the emergence of the individual self and its limitations. They include:

(1) / (6) Māyā Tattva: The Source of the World

In most other spiritual traditions, the word Māyā is associated with "illusion" or "delusion." However, in Tantra, this term takes on a different and more positive meaning. Although Māyā leads us to perceive duality where there is actually unity, this perspective is essential for our self-discovery. The Divine itself chose this process in creating the universe.

Māyā is the expression of Śaiva-Śakti to bring forth creativity and diversity. Thus, Māyā becomes the "source of the world" (jagad-yoni). Māyā is a fundamental force through which the Divine projects itself into manifestation. This force enables distinction and differentiation, causing the One to appear as many.

The paradox of Māyā is that it both separates and connects. It creates differences and presents challenges. Yet, this very force is used by the Divine to reveal itself. Māyā, in its divine form, expresses the entire visible reality. It gives us the opportunity, through worldly challenges, to gain deeper insights into unity despite diversity.

(7) - (11) The Five Veils (Kañcukas)

Māyā further divides into five veils (Kañcukas), which limit or conceal the divine attributes. The veils consist of:

/ 7) Kalā: The limited power of action or restricted power.

- / 8) Vidyā: Limited knowledge.

- / 9) Rāga: Desire or longing. The urge to fulfill the need to recognize one's true nature.

- / 10) Kāla: Time and the transience conditioned by time, as well as the awareness of the past and future.

- / 11) Niyati: Destiny and the binding to the cause-and-effect principle of karma.

Aśuddha Tattvas (Impure Tattvas)

The impure Tattvas (Aśuddha Tattvas) are directly taken from Sāṁkhya philosophy. It shows a certain confidence that Tantrism classifies these principles as gross material compared to the principles characteristic of it.

In the Tattva system of Sāṁkhya philosophy, Puruṣa comes first. In this sense, Puruṣa is synonymous with Śiva in the Tattvas of Tantrism. However, within Tantrism, Puruṣa is relegated to the subtlest place among the elements that make up our physical experience. Often, Puruṣa is also depicted in the Tattvas of Tantrism at the lowest position among the Śuddhāśuddha Tattvas.

The Aśuddha Tattvas include, initially, a duality of self and matter:

(1) / (12) Puruṣa Tattva: The Principle of the Individual Self

In Sāṁkhya philosophy, Puruṣa refers to the intangible essence of our individuality. However, it is completely separate from the material form of our individuality, yet eternal, unaffected by time.

In Tantra philosophy, on the other hand, Puruṣa is the conscious essence of our individuality. Here, Puruṣa is now transient. It is only a phase of contraction that dissolves through the expansion of consciousness.

(2) / (13) Prakṛti Tattva: The Principle of Nature or Matter

The term Prakṛti Tattva refers to the principle of nature or matter, considered fundamental to the manifestation of all physical forms and phenomena. In Sāṁkhya philosophy, Prakṛti is viewed as the original and immutable cause of all material existence. It is shaped by the constant interaction and balance of the three Guṇas: Sattva (the pure), Rajas (the active), and Tamas (the solid). These three qualities are dynamic and constantly influence the changes in nature.

It is important to understand that Prakṛti in Sāṁkhya philosophy serves as the fundamental substance for all manifested and embodied forms—it is essentially the "building material" from which the world is developed. In this sense, Prakṛti can be seen as the first form of materiality.

In Tantra, however, a slightly different perspective is taken: Here, the primary source of the manifested world is not Prakṛti but Māyā. Māyā is the force that generates duality and plurality. Through Māyā, the diversity of forms arises, and it initiates the process of the contraction of consciousness. In this view, Māyā is the driving force behind the creation of differences and forms in the manifested world, while Prakṛti provides the material substance from which these forms arise.

This distinction is central to understanding the different perspectives on Prakṛti in Sāṁkhya philosophy and Tantra. While in Sāṁkhya, Prakṛti forms the basis of all material phenomena, tantric thought adds another dimension by considering Māyā as the initial cause of the manifested world and its associated duality.

(14), (15), (16) The Three Elements of Citta

Following are three elements that make up our mind (Citta):

- / 14) The Knower or Intellect (Buddhi)

- / 15) The Ego (Ahaṁkāra)

- / 16) Thinking (Manas)

Buddhi recognizes, Ahaṁkāra relates the recognized to itself, and Manas processes the sensory impressions.

In the Sāṁkhya-Kārikā, the word "Citta" does not appear (unlike in the Yoga Sūtra). And since these three Tattvas belong to the realm of Prakṛti, they are, in the dualistic Sāṁkhya philosophy, devoid of consciousness. In non-dual Śaiva Tantra, this is different. Citta is—like everything—an expression of universal consciousness in a contracted form and thus conscious.

There now follow four groups of five: Sense organs (Jñānendriyas), action organs (Karmendriyas), subtle elements (Tanmātras), and gross elements (Mahābhūtas). The sense organs, action organs, subtle elements, and gross elements are assigned to each other according to their sequence. Specifically:

(17) - (21) The Five Sense Organs (Jñānendriyas)

- / 17) Ears with hearing

- / 18) Skin with feeling

- / 19) Eyes with seeing

- / 20) Tongue with tasting

- / 21) Nose with smelling

(22) - (26) The Five Action Organs (Karmendriyas):

- / 22) Mouth with speaking

- / 23) Hands with touching

- / 24) Legs with walking

- / 25) Sexual organs with reproduction

- / 26) Excretion

Here we find a peculiarity and a difference from the 25 Tattvas of Sāṁkhya philosophy. There (in the Sāṁkhya-Kārikā), the two action organs (4) and (5) are swapped. Excretion thus occupies the 4th position, while reproduction is in the 5th position.

Sāṁkhya-Kārikā 26:

buddhīndriyāṇi śrotratvakcakṣūrasananāsikākhyāni /

vākpāṇipādapāyūpasthān karmendriyāṇy āhuḥ // ISk_26 //

The sense organs are called ear, skin, eye, taste, and nose.

Speech, hands, feet, anus, and generative organ are called the action organs.

In Sāṁkhya philosophy, excretion corresponds to the gross element of water, while reproduction corresponds to the gross element of earth. However, in the order found in many contemporary publications on the Tattvas of Tantrism, reproduction corresponds to water, while excretion corresponds to earth. It is worth noting that the sequences in the source texts of non-dual Śaiva Tantra generally vary.

(27) - (31) The Five Subtle Elements (Tanmātras):

- / 27) Sound

- / 28) Touch

- / 29) Form

- / 30) Taste

- / 31) Smell

(32) - (36) The Five Gross Elements (Mahābhūtas):

- / 32) Space

- / 33) Air

- / 34) Fire

- / 35) Water

- / 36) Earth

Classification of the Tattvas

These 36 Tattvas provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexity of reality and the relationship between the Divine and the material world. They also offer a basis for spiritual practices aimed at overcoming limitations and recognizing the original, pure consciousness.

Images: OpenAI

Dr. Ronald Steiner

Dr. Ronald Steiner

Bärbel Münchow

Bärbel Münchow

Messages and ratings